Domaine de Kerguéhennec

For more than 40 years, Mel Bochner’s work has been contrasting programme and execution, anticipatory rigour and methodological unpredictability. For this Conceptual art pioneer, who has also been (for Arts magazine and for Artforum) a witness to and chronicler of the various changes going on in the New York art world, as from the last gasp of Abstract Expressionism, one and the same orderly sequence of operations never culminates in the same outcome. All manner of procedure is to be found in the activity of counting, for example. Likewise, measuring a surface offers an infinite number of variants. Language, lastly, devoted to exploring the world, has its own phenomenal density. These, then, are three ways of understanding reality for which Mel Bochner has shown a preference since his earliest days: counting, measuring, describing. And instead of seeing in these tools, which are available to all and sundry, irrefutable abstract methods for thwarting the snares of the concrete, instead of counting on the universal to get a better grasp of the local, Bochner’s approach is intended to be completely subjective; it is accordingly enriched by his own discrepancies, thus in stark contrast with the bogus radicalness of some of his contemporaries, and boasting no good conduct certificate when the artist quotes the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Bochner has been an eminent (and formidable) teacher at Yale University, but he has never laid claim to the title of professor of philosophy. “Language isn’t transparent”, he observes, self-mockingly. Now, this truism that is being forever recoined sheds some light for us on the most dubious aspiration of certain artists to a “pure” form of conceptualism, For Bochner, pragmatic artist that he is, the gesture also gets its turn to speak, and subjectivity is expressed precisely where least expected. Any attempt to gain a better knowledge of the world is besmirched by approximations. And it is this ongoing and tentative groping that Bochner's oeuvre presents.

The thematic retrospective that has just been devoted to Mel Bochner at the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the greatest of American art museums, focused on his works as they relate to language. The Domaine de Kerguéhennec does not intend to be more exhaustive or thorough–it will deal with everything. The exhibition under preparation comes, incidentally, at a particularly interesting moment in Bochner’s oeuvre, as the artist takes back his freedom, as it were, weary of being identified solely with his wall diagrams of numbers, which brought him to notice, and which he is certainly not turning his back on--for he was tempted by colour in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and has made lavish use of it since the 1990s. By introducing wit and colour into his works, Bochner in no way takes away from their penetration, originality and precision. By flirting with the flaw of taste, he frees himself from any kind of cant and cliché.

This is the first solo show to fill all the areas of the contemporary art centre. There will actually be three exhibitions for the public to visit, all offered in the guise of invitations to discover Mel Bochner’s work.

In the Kerguéhennec sheepfold there will be a set of pictures belonging to the Thesaurus Paintings series produced in the 2000s, which has never been hung and presented in quite such a comprehensive way. Painted in eye-catching colours in the style of advertising and fashion (from babywear to bikini collections!), based on more or less credible variations (which are, as a whole, quite hilarious) of synonyms which the artist has previously compiled in notebooks, these recent pictures call to mind the lists of words and adjectives written on squared paper, intended as psychological portraits which Bochner made in 1966 when, at the beginning of his career, his work wavered between minimalist sculpture and what was not yet called the conceptual “statement”. What hallmarks the Thesaurus Paintings is not just their colours, formats, and media, and the use of oil paint instead of a fountain pen, but rather their psychological bent. When Bochner produced the portraits of Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson, Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd and Eva Hesse, whom he often hung out with in the 1960s, he was paying them a discreet but serious tribute. Nowadays, when he decides to embark on a picture with the put-down adjectives: Lazy, Lethargic, Crazy, Vulgar and Irascible, Bochner is acting as a painter-cum-satirist, and if he permits himself to dwell on the least glittering features of a character, this is because his pictures are halfway between the photofit picture of a generic artist who is out of inspiration, and... the self-portrait!

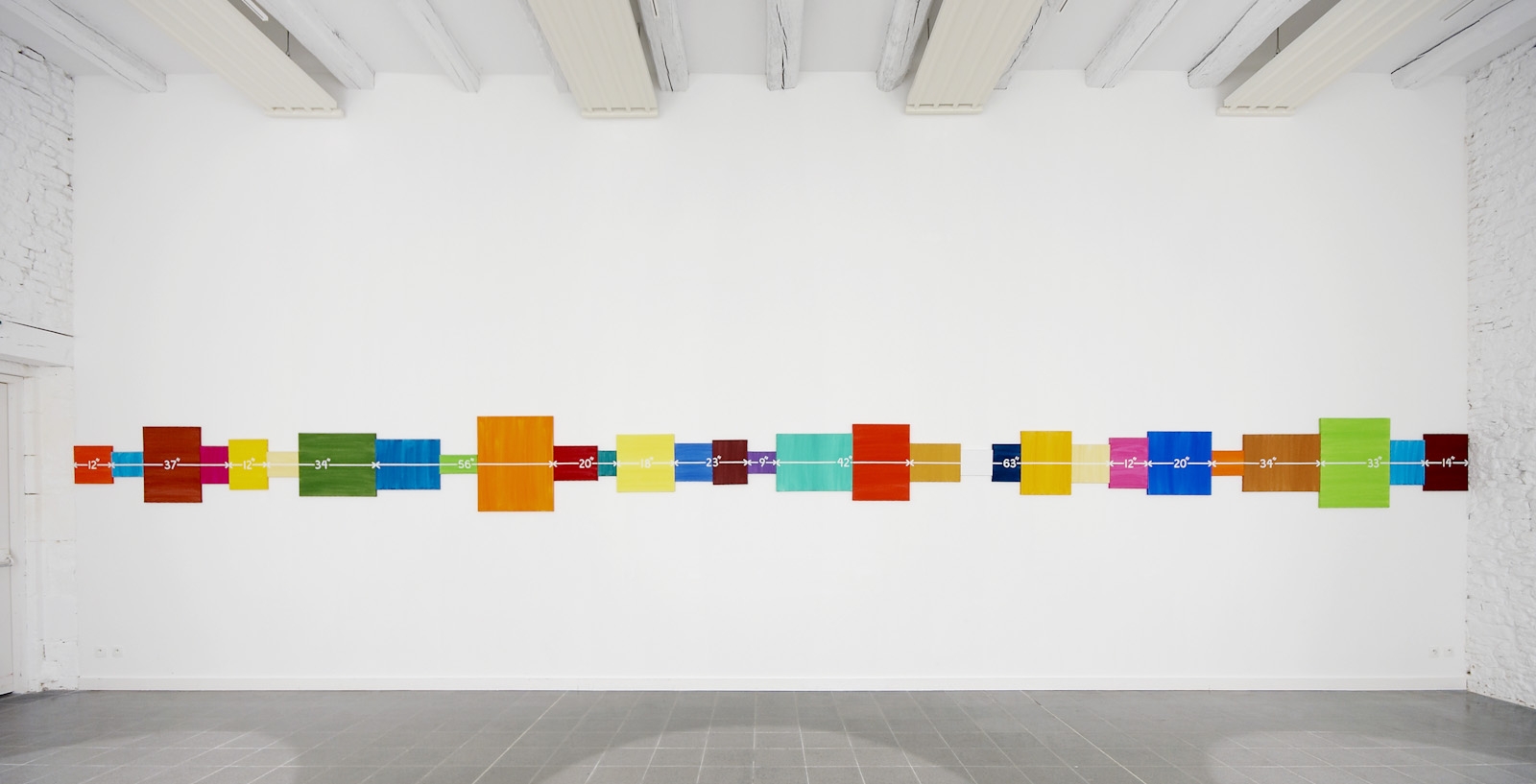

In the Kerguéhennec stables, turned into something akin to a huge “tube” by three large rooms leading into each other, after words it is numbers that will guide the visitor. Here, you will discover a recapitulation of the last ten years, thanks, in particular, to loans from the National Contemporary Art Collection [FNAC], the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Geneva, and the Burgundy Regional Contemporary Art Collection [FRAC Bourgogne], while one specific piece will be produced on the largest picture rail and two geometric diagrams from 1971 and 1972 will be shown on the floor.

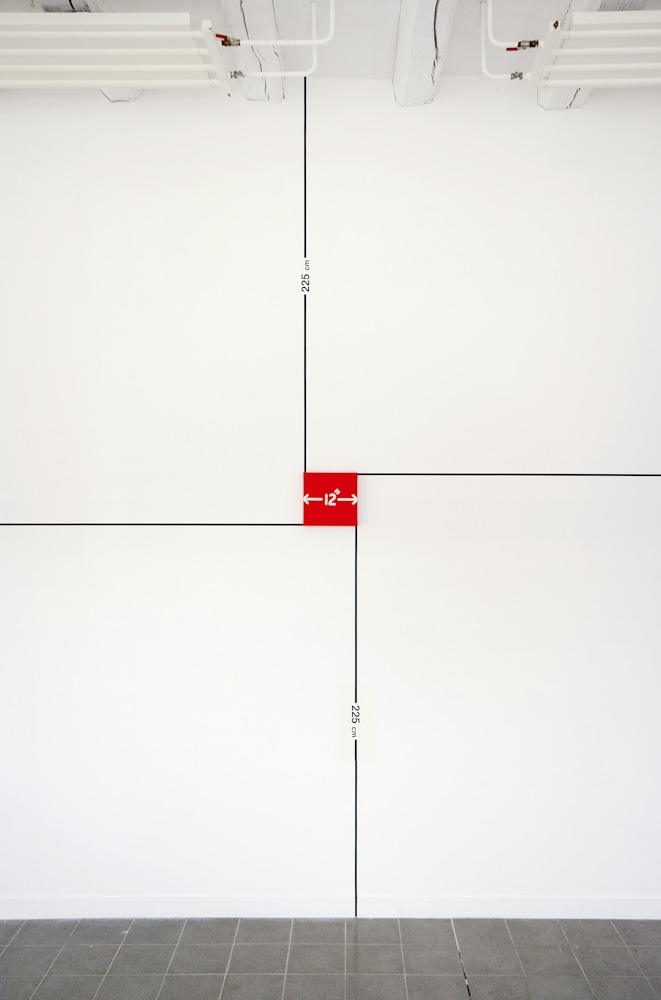

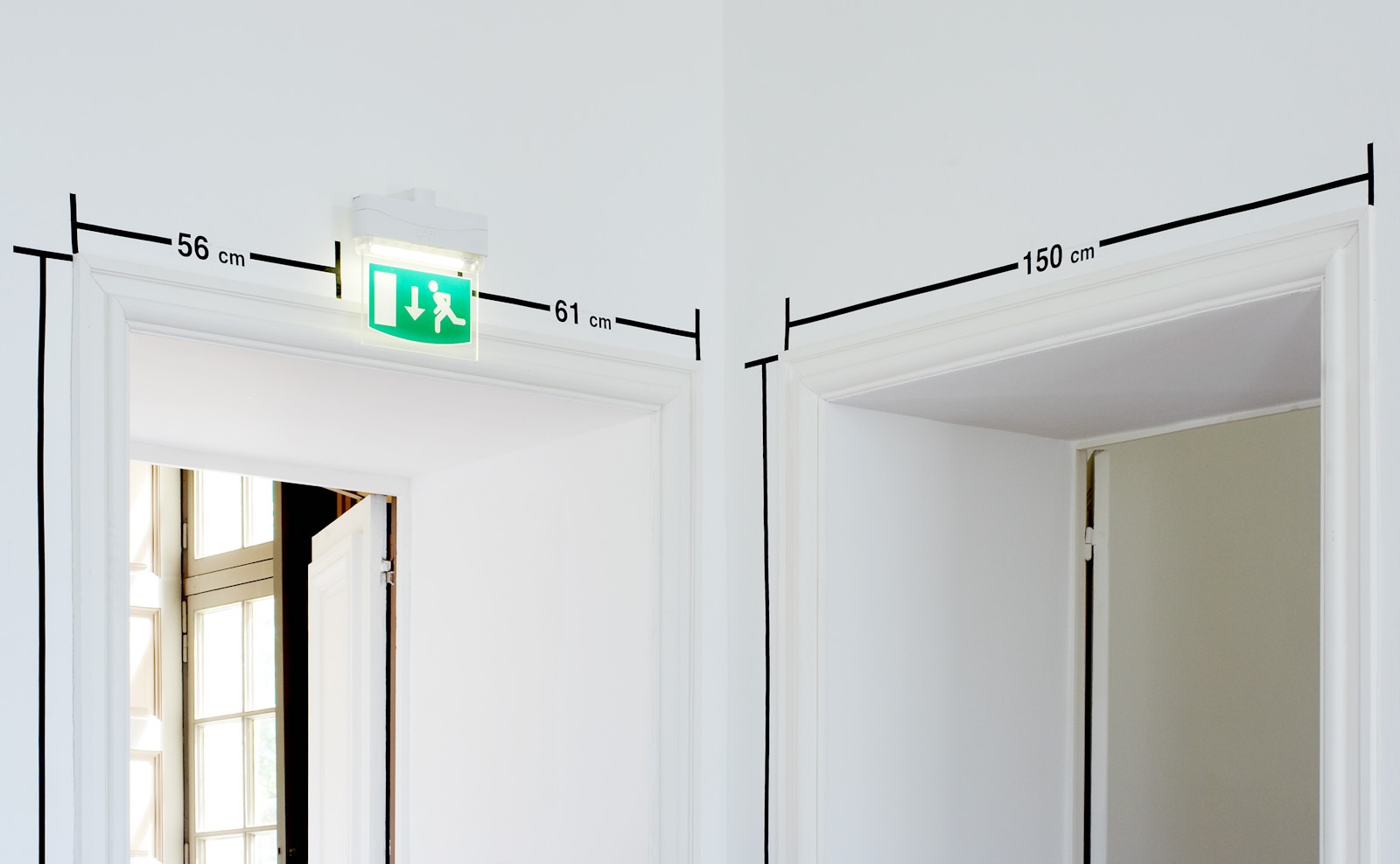

For the castle itself--recently restored--Mel Bochner has come up with a “made-to-measure” wall installation. What he has actually done is reactivate the procedure for the Measurement Pieces, as applied in situ, for one or two gallery shows in the late 1960s, extending the process here to all the rooms on the upper floor, and in proportions never hitherto attempted. The principle could not be simpler: the walls are “highlighted” with numbered arrows and indications tallying with their real measurements. The mathematical norm informs the specific domestic setting. The space in effect becomes the real place at the same time as the three-dimensional blueprint of the real place discovered in the draft state. The building delivered back to the public after several years of restoration work thus, to his eye, keeps a virtual aspect. This impression is bolstered by the place’s seasonal opening programme, and by the thrill that invariably accompanies having free access to an ancient private residence.

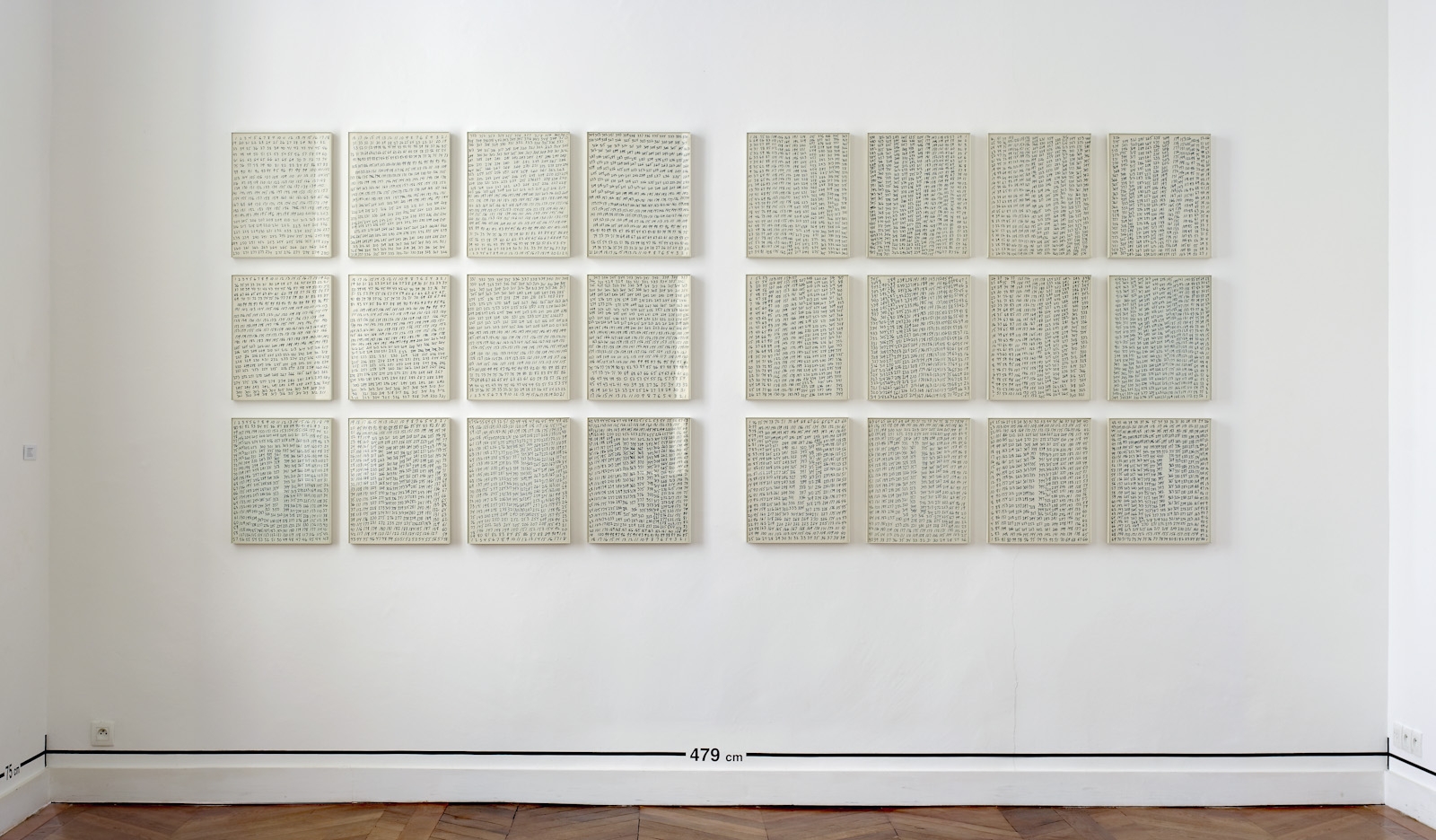

In the installation designed by Mel Bochner, not only each wall, but also each and every detail of the inside arrangement will thus reveal its real dimensions. Just four rooms will house other works in addition to these indications. In one of them there will be a presentation of 24 Reading Alternatives, an outstanding series of 1971 drawings on loan from the National Museum of Modern Art/Pompidou Centre. Another room will be showing a geometric variant from the same year: Counting Alternatives (The Wittgenstein Illustrations). As visitors stroll about at random they will find, further on, set on a stand, a filing cabinet containing a compilation of photocopies of real Bochner drawings mixed with technical diagrams with plenty of millimetered indications: Measurement: Projects and Drawings, 1968-1972-2007. (It is not always easy to tell these works apart, and the artist has shuffled the cards less to muddle us than to bid us to pay ever greater heed). Lastly, in the smallest room of all, two photographic self-portraits from 1968 will be on view; in them the artist takes as his scale of measurement his very own body in front of a building: Actual Size.

Frédéric Paul